The new Pixar film explores adolescence by bringing its complicated feelings to life.

BY DEMOND HILL JR. | JUNE 18, 2024

In 2015, Inside Out hit theaters and soon became renowned for its creative and scientific brilliance. In the movie, nine-year-old girl Riley moves with her mother and father from Minnesota to San Francisco, which means she needs to navigate a new life–social, school, and home.

The emotion characters from Inside Out 2: Ennui, Anxiety, Embarrassment, Envy, Joy, Fear, Disgust, Anger, Sadness

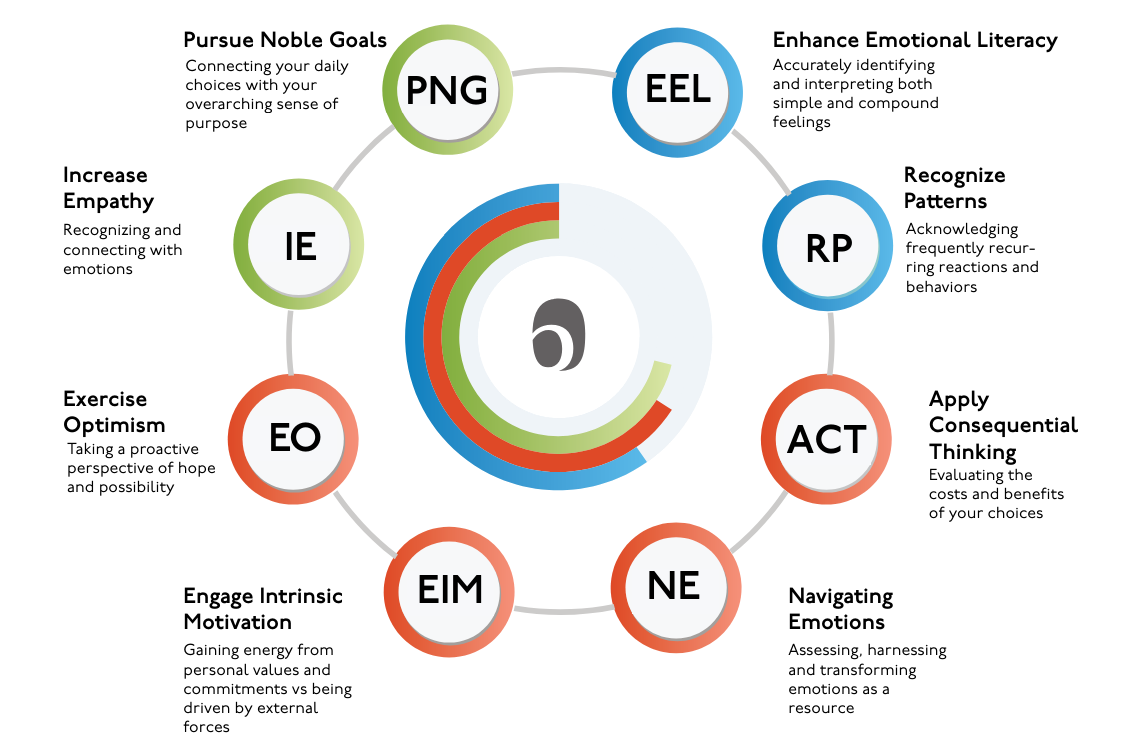

Riley’s primary emotions become characters in the movie, each with their own personalities: Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust. The story largely takes place inside Riley’s head, in a place called Headquarters, where these emotions work together to help her to find her way in a new city–and to achieve a balanced emotional state.

Inside Out is more than just an animated film. It’s a thoughtful and profound exploration of the human emotional experience, highlighting the importance of all emotions, not just happiness, for one’s positive well-being. By creatively and empathetically portraying the inner workings of Riley’s mind, Inside Out reminds us that understanding and embracing our emotions while prioritizing positive relationships fosters a sense of safety and belonging despite the challenges we encounter.

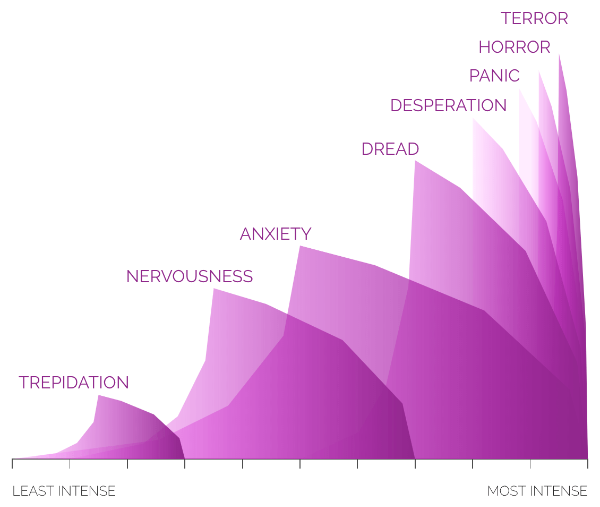

This past Friday, Pixar released a sequel to Inside Out. In part two, Riley is now thirteen years old and she’s pushed into a new development stage, which brings to life new emotions inside of her: Anxiety, Ennui, Nostalgia, and Embarrassment, each one a complex character in its own right. She is changing. Her body is changing. Her mind is changing. Her social world is changing. As time passes and interactions unfold, her body or emotions keep the score and are reflected in her everyday behaviors. On her journey, Riley feels true pain, hurt, remorse, and, most importantly, grief—the grief of her past self–and the grace required to heal, along with the challenges of unconditionally loving the new self.

As many Greater Good readers already know, Pixar turned to the Greater Good Science Center and our faculty director (and my mentor), Dacher Ketlner, for help in grounding Inside Out and its sequel in the science of emotion. And indeed, science and art converge ever so gently in these two movies, reminding us of our innermost and outer (childlike) selves. But, when you look closer to the margins, major question is raised as a critical emotion science scholar: what does the new movie reveal about the science of our emotions, and what or who was left out of the film?

The beauty of emotion science on screen

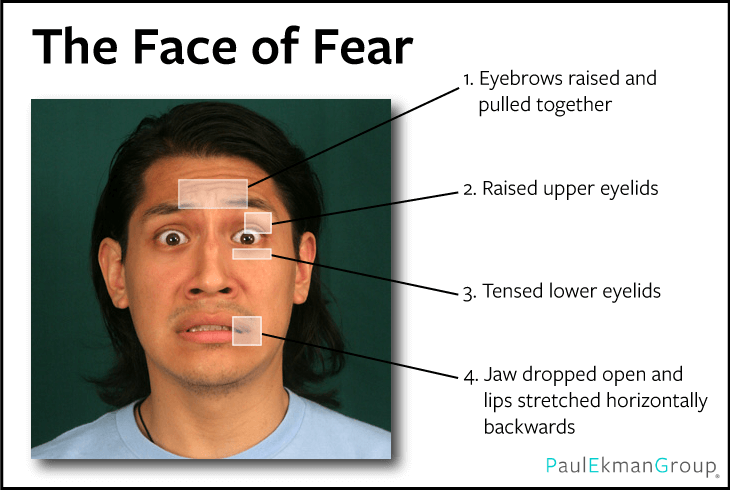

While many scientists agree that emotions are universal and inherited, more and more scholars see how they are expressed as very social. These researchers study how our daily interactions with others shape our feelings, thoughts, and actions.

In the film, Riley’s emotions are influenced by her interactions with others and her social environment, like a hockey camp with high-school girls. Riley is shown to be easily influenced by the social expectations around her. The first Inside Out movie suggests that emotions are linked to past experiences, especially in how childhood experiences shape our understanding of feelings, ourselves, and the world.

In the new movie, Riley’s emotions intensify as she tries to maintain her relationships with her best friends while trying to impress a new group of friends. This storyline demonstrates how social expectations and norms affect our emotions and behavior as Riley shifts between the two groups.

The film emphasizes that emotions are key to communication, and her emotions help Riley build and repair relationships with her peers. Emotions/characters like Fear, Disgust, Anger, and Embarrassment act as signals to protect her in different situations, like pulling away after realizing she held her friend Val’s hand for too long. Inside Out 2 clearly shows that emotions are social and serve social functions, demonstrating that our interactions, cultural backgrounds, and everyday experiences shape our feelings.

There are also sociological perspectives on emotions. In the early 1980s, sociologists focused on feelings and emotions, exploring their role in human motivation and social structures. Many argue that emotions are inherited and biological but still shaped by historical, social, and political contexts. Although Inside Out 2 doesn’t explicitly follow this sociological view, it aligns with Arlie Hochschild’s “Emotional Labor” and “Feeling Rules” concepts.

Emotional Labor is about managing feelings and behaviors to show certain emotions publicly, often to fit in or be accepted. Feeling Rules are social guidelines that tell us how and when to feel certain emotions, varying across different contexts. In the film, Riley adjusts her emotions to get positive reactions from others, and she follows social-feeling rules, which increases her anxiety.

That concept is rarely applied to children, but my own “Emotion as Play” research examines how young African American people use Emotional Labor and Feeling Rules. Watching the film, I realized that emotional labor is like a weight people carry, and they need social, emotional, and physical effort to manage it. Riley’s struggles with moving into different spheres and fitting into them show how these pressures build up over time, affecting her deeply. In this way, Inside Out 2 highlights that adolescence is a critical time when mental health issues often become more noticeable and intense.

The scientific power of the humanities

Inside Out 2 is such a beautiful display of science and art. It opens our minds to possibilities and reminds us of how central emotions are to our humanity. However, the film missed a vital opportunity to bring to light the real stars of the show, who seemed to have been pushed out on the margins. Just where are Love, Grace, and Empathy?

While some argue that love is not an emotion in the strictest scientific sense, both science and the humanities have long considered Love–along with Grace, and Empathy–as crucial to the development of communities of wellness. By using research from the humanities, we can see how they appear in the film and how they could help build families and communities that focus on mental health and well-being. Inside Out 2 hints at these deeper connections and helps us to understand what they reveal about ourselves and each other–and they led me to reflect on how the movie highlights certain concepts from science and the humanities

A Critical Love Ethic: This is a conception of love that requires truth, understanding, and acceptance. Through her various moments, Riley was forced to sit with herself–as she spent time tossing and turning in her bed alone, her mind working, her emotions intense. It seemed like the only thing that freed her from herself and the expectation of her environment was love from her best friends Bree (of African descent) and Grace (of Asian descent). These two possess what thinkers like bell hooks, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison refer to as a Critical Love Ethic.

As bell hooks outlines, Riley is suffering from the oppressive forces of societal expectation or pressure that led to the distortion of her sense of self and, most importantly, her connection to herself. Critical Love Ethic is a counter-cultural idea that argues for collective resistance to the social norms, feelings rules, and social expectations that lead to the suppression of emotions to help create a society of human flourishing. A Critical Love Ethic equates love with strength, courage, and truth, which was displayed beautifully by both Bree and Grace as they, through the power of love, bridge differences and provide Riley the reassurance to feel safe but held accountable for her behavior without further embarrassment.

Although I yearned for love throughout the film, I found my moments and rejoiced in it because I had the chance to witness young people practice a Critical Love Ethic. Integrating love into children’s or youth films is not a superficial act but a radical act of care, compassion, and belonging that will have the power to change the world around us for all.

Grace Abundance: Grace is a multifaceted concept that encompasses love, gentleness, and a sense of inner peace and disrupts traditional definitions. In many eyes, Grace is something we all need to show others and show ourselves as the world around us gets faster and more complex. Many of us have the weight of the world on our shoulders–with stress compounding and trauma continuing to increase, taking a tremendous toll on our mental health. We are sometimes hardest on ourselves –when we do not meet expectations and deadlines or show up as our best selves. Grace is the ability to slow down, get grounded, and speak life into the nooks and crannies of your imperfections–because for others, your imperfections are beautiful, too.

Riley needs some Grace (literally and emotionally) in her life to ease the weight she carries trying to be all the things all at once. But, as marginalized groups have always done due to the realities of an unjust world, we rely on unique, often not spoken or understood emotions to uplift and, at times, resist in order to thrive. Riley’s best friends extend Grace to her, reminding her that their love is unwavering, that their care is unconditional, and that it will simply be okay. It seems to me that Inside Out 2 missed an opportunity in not explicitly naming and making space for Grace in Riley’s story.

Empathetic Desires: Empathy is the ability to understand why someone feels the way they do, why they are doing the things they do, and how that is informed by who they are as an entire person (e.g., identity, lived experiences, upbringing). Empathy requires sensitivity to the world, a desire for a deep sense of connection, and acknowledgment that other people are different from you and have different feelings.

When individuals truly understand and feel what someone else is going through, they are more likely to offer support, comfort, or assistance. This compassionate response is fundamental in nurturing and sustaining personal and professional relationships. Riley, through her ups and downs, is extended empathy by those around her, even those who she is trying to impress, like her new friend Val, who was a simultaneous source of anxiety and comfort.

Despite Riley’s awkward and quirky behavior, Val is gentle to her, comforts her, celebrates her, and cares for her. She simply wants Riley to be herself and not conform to the expectations that are both explicit and implicit. In the end, Inside Out 2 reminds me of James Baldwin’s liberating words in The Fire Next Time: “Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within. I use the word love here not merely in the personal sense but as a state of being or a state of grace—not in the infantile American sense of being made happy but in the tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth.”

Demond Hill Jr. is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Social Welfare at the University of California, Berkeley. His research focuses on the mental health and emotional well-being of Black children and youth, their families, and communities.

© 2024 The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley