John Ford's "From Reaction to Response" explores the distinction between reactive and responsive approaches to conflict. Reactive responses, stemming from unconscious emotional triggers and past experiences, involve blame and victimhood. Responsive approaches, conversely, emphasize taking responsibility for one's emotions and consciously choosing how to react. The author advocates for emotional awareness and the rewiring of ingrained reactive patterns to foster healthier conflict resolution. This involves acknowledging and processing emotions without judgment to break destructive cycles. Ultimately, the text argues that shifting from reaction to response requires conscious effort and self-awareness.

This recording was generated by Notebook LM based on the article I wrote in March 2008, the full text of which appears below:

From Reaction to Response: Conflict As A Choice

By John Ford

March 10, 2008

Once we embrace that conflict is inevitable in social relationships, the question we have to ask is “how do we respond?” Responsibly, we’d hope. Yet, for the most part, when we are in conflict, we are not very responsive, and tend to be reactive. Shifting to a responsive approach to conflict is easier said than done. When we are in conflict situations, we are typically being triggered and reverting to our unconscious conflict handling scripts.

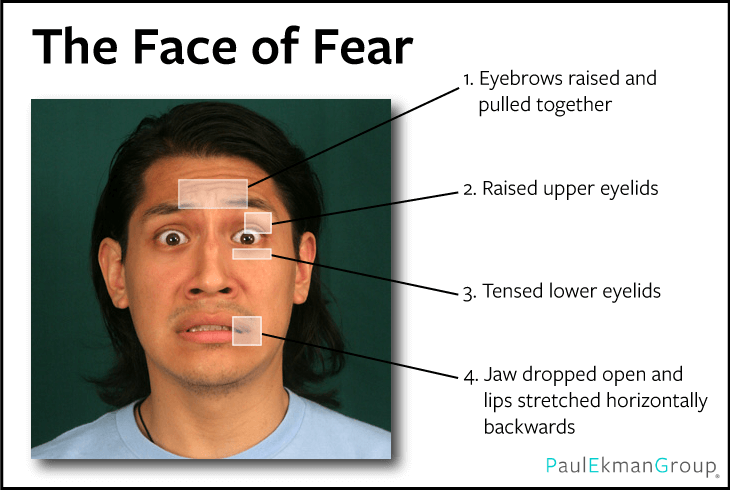

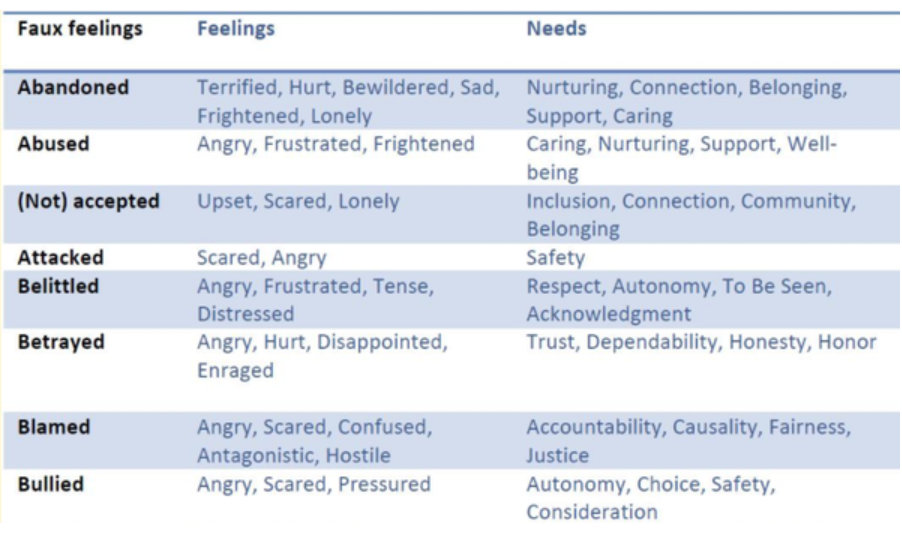

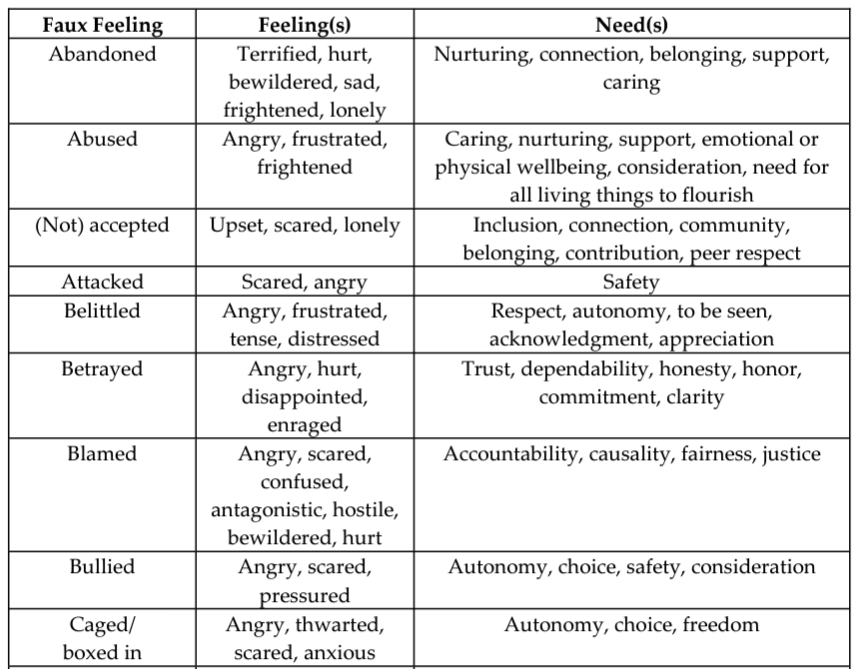

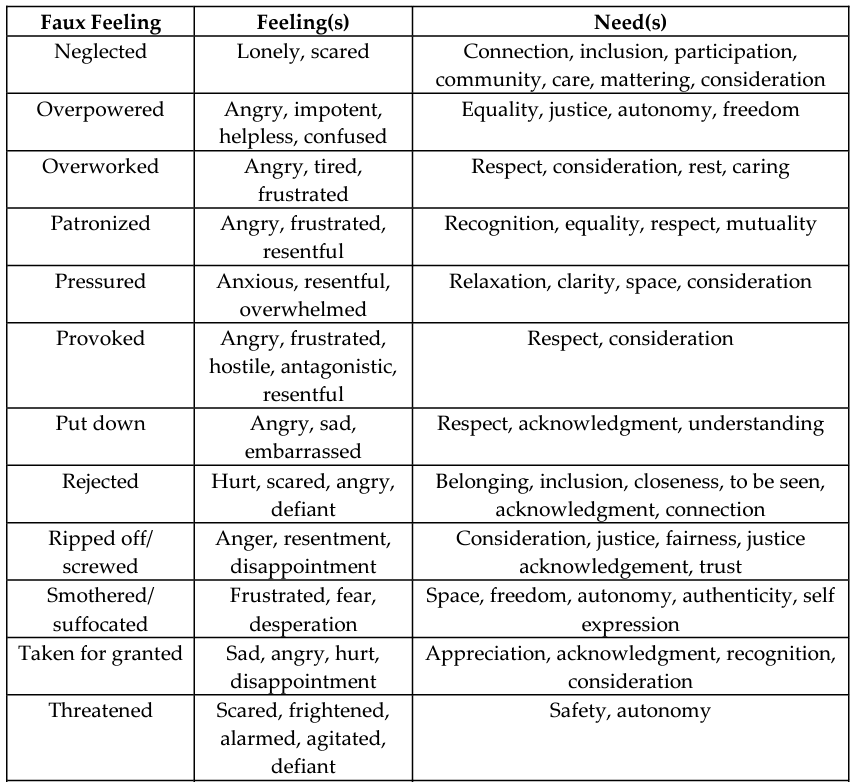

What’s the difference between a responsive and a reactive approach? When we respond to the challenges of life-including our conflict situations-we take responsibility for our role in the situation, we are in tune with what we are feeling and why, and our thoughts, words and behaviors are conscious of the bigger picture. By contrast, when we react, we shift responsibility for the situation to the other through blame; we assume the victim role and are ‘justifiably’ carried away by powerful feelings like anger, fear and grief. We use an unconscious template for reaction that seeks acknowledgement, justice, restoration, and even revenge.

One of the reasons that it is so hard to be responsive is that we experience and are typically exposed to unproductive conflict scripts from the time of our birth. Our earliest lessons come from the approach our parents take to their own conflict, our experience of how our parents deal with us, and as we grow up, through our interactions with siblings, friends, colleagues, teachers and bosses. If we struggle to deal with our differences with the aid of language, try and imagine how hard it was during those early pre-verbal years when we didn’t even have a word to describe conflict.

As a species we have achieved great physical and mental milestones, and yet when we are threatened by another’s behavior-as is typically the case in conflict-we reveal how immature we are emotionally. It is as if we revert to our childhood mentality when we are triggered.

Knowing this at an intellectual level is one thing. Being able to shift our physical and emotional behavior from reaction to responsive choice when we are actually triggered is another. If only, because when we are triggered, we are by definition not in our most conscious state. Our well worn neural pathways take us away from the perspective taking cortex, into the reflexive limbic structures such as the amygdala. We are in a reactive survival mode.

As modern neurologists, such as Antonio Damasio, have helped us understand, emotions are enmeshed in the neural networks of reason. In other words, there is no such thing as a decision free of emotion. Yet in our culture, we continuously hear expressions that extol the virtue of not making emotional decisions. This is one of the great challenges of our time-how to mature emotionally, such that we can make responsible emotional decisions about how to deal with our differences (aka conflict).

There are two ways we can approach our penchant for reactivity. One focuses on the moment that we are triggered, and seeks to restore short term balance. It is really the symptomatic response-the band aid-that helps the person in conflict calm down, and release the primal grip of the amygdala so that the cortex can come into play. There are a variety of calming techniques that help with this. Until the next time we are triggered!

The other is more causal and seeks to transform the trigger mechanism itself. This approach is centered on taking responsibility for our own emotions and learning new templates for our emotional responses. It relies on the inherent plasticity of the brain to rewire its well worn templates.

Stuff happens. We all experience pain and discomfort. The shift is in seeing that when we are triggered, it is not because of something out there that is happening, but rather the interpretation we give to the situation. A blue sky can mean hell for a farmer desperate for rain, and joy for a sunbather at a beach. What triggers one, will not necessarily trigger another. Playing the victim is a choice. And when we do, it feeds into our tendencies to react.

If we can make the shift from victim to navigator of the quality of our own experiences, we can start to work with the energy of the emotion. So often we suppress what it is that we are feeling, or just give our emotions free reign. Both of these reactions are tempting, but do not help shift the trigger mechanism. In fact the unresolved emotional energy continues to seek release and sets in motion the characteristic spiral dynamic of destructive conflict.

Gestalt therapy has a simple suggestion for change-feel what you are feeling. It is only when we are able to experience where we are emotionally that we can move somewhere else. Some find this scary. Imagine, allowing yourself to feel the anger. Almost immediately you tell yourself to be bigger, and to show compassion. Or if you are disappointed at a friend, you chastise yourself for being judgmental. Yet, to change the way we are triggered, we must allow ourselves to feel what it is that we are feeling.

This does not mean that we wallow in our feelings. We use the attention of our mind to focus and clearly identify what it is that we are feeling. If we are able, we trace back in time, other experiences where we were triggered in a similar manner. You have probably heard people asking in exasperation, “why does this keep happening to me?” It is because they are carrying unresolved emotional energy that in all probability will take them back to an incident that occurred in the earliest years of their lives.

Once we have identified the emotional signature that we associate with the trigger, and explored its commonality with other life experiences, we can allow ourselves to feel the emotion, ideally with a mind that is compassionate. In other words, we do not judge ourselves for what we are feeling. When we can do this, the energy of the emotion can move, and not be hijacked by limiting neural structures like the amygdala.

When we allow our feelings, when we start to experience them fully, and to welcome them into the neural hallways of reason, we can start to respond in a more mature way to our life challenges. We are able to take the stock of the bigger perspective and incorporate the significance of what is happening to us right here, right now.

As long as we have unresolved emotional energy, we will always be triggered by this or by that. Each of us discovers through his or her triggers, the areas that seek integration. When we allow these situations to morph into conflict situations, we have choices. One path takes us toward the well worn templates of reaction. Another takes us toward calming techniques, and ways that work with (not against) the energy of the emotion.

This path is not easy, for in the moment of being triggered we are outraged that we are being treated the way we are. The situation in our mind rises to a level that demands a reaction-and when we don’t get the ‘response’ we expect, our ire only increases, and we set in motion the destructive cycles that we ultimately call conflict. A shift that is honest about our proclivity for reaction and which moves us toward-not away- from our emotions increases our chances of a conscious response to the challenges of the inevitable conflict that comes our way.

Being aware of the difference between a reactive and responsive approach is the start. Then the hard work begins. As we uncover the contours of our unconscious conflict handling scripts we can begin to shift. We learn how to calm down, to take responsibility for our reactions, and hopefully to feel what is going on a wholesome manner that doesn’t exclude our most creative problem solving capacities.