What I wanted to share, was their definition of empathy and it’s practical benefits to the world of negotiation.

***

“Empathy

For purposes of negotiation, we define empathy as the process of demonstrating an accurate, nonjudgmental understanding of the other side’s needs, interests, and positions.

(As is common in legal journals, there are a lot of footnotes. Here’s what the author’s added in theirs in relation to this first sentence:

The notion of empathy is and always has been a broad, someone slippery concept — one that has provoked considerable speculation, excitement and confusion. The term ‘empathy’ is of comparatively recent origin. It was coined by an American experimental psychologist in 1909 as a translation of the German word Einfühlung, defined as .to feel ones way into. Over the last 80 years, many subdisciplines in psychology adopted and modified the term, giving it a range of definitions and connotations.

Contemporary scholars debate such issues as whether the content of empathy is cognitive or affective — whether we understand the thoughts, intentions, and feelings of others or contemporaneously experience them. Similarly, scholars question whether the empathic process is primarily cognitive ‘thinking it through’ or affective ‘feeling it through’ )

There are two components to this definition.

The first involves a skill psychologists call perspective-taking trying to see the world through the other negotiator’s eyes.

The second is the nonjudgmental expression of the other person’s viewpoint in a way that is open to correction.

In crafting this definition, we have found useful the work of Carl Rogers. Rogers described empathy as:

“Entering the private perceptual world of the other and becoming thoroughly at home in it. It involves being sensitive . . . to the changing felt meanings which flow in this other person. . . . It means temporarily living in their life, moving about in it delicately without making judgments, sensing meanings of which they are actually aware. . . . It includes communicating your sensings of their world as you look with fresh and unfrightened eyes at elements of which the individual is fearful. It means frequently checking with them as to the accuracy of your sensings, and being guided by the responses you receive. . . . To be with another in this way means that for the time being you lay aside the views and values you hold for yourself in order to enter into another world without prejudice.”

For Rogers, empathy involved the process of nonjudgmentally entering another’s perceptual world.

For us, it also involves the active expression of this understanding of the other side.

Defined in this way, empathy requires neither sympathy nor agreement.

Sympathy is ‘feeling for’ someone — it refers to an affective response to the other persons predicament.

For us, empathy does not require people to have sympathy for others plight.

Instead, we see empathy as ‘a value-neutral mode of observation’, a journey in which we explore and describe another’s perceptual world without commitment.

Empathizing with someone, therefore, does not mean sympathizing with, agreeing with, or even necessarily liking the other side.

Instead, it simply requires the expression of how the world looks to that person.

The benefits of empathy relate to the integrative and distributive aspects of bargaining.

Consider first the potential benefits of understanding (but not yet demonstrating) the other sides viewpoint. Skilled negotiators often can "see through" another person’s statements to find hidden interests or feelings, even when they are inchoate in the others mind.

Perspective-taking thus facilitates value-creation by enabling a negotiator to craft arguments, proposals, or trade-offs that reflect another’s interests and that may create the basis for trade.

Perspective-taking also facilitates distributive moves. To the extent we understand another negotiator, we will better predict their goals, expectations, and strategic choices.

This enables good perspective-takers to gain a strategic advantage analogous, perhaps, to playing a game of chess with advance knowledge of the other sides moves.

It may also mean that good perspective-takers will more easily see through bluffing or other gambits based on artifice. Research confirms that negotiators with higher perspective-taking ability negotiate agreements of higher value than those with lower perspective-taking ability.

The capacity to demonstrate our understanding of the other sides viewpoint to reflect back how they see the world confers additional benefits.

Negotiators in both personal and business disputes typically have a deep need to tell their story and to feel that it has been understood. Meeting this need, therefore, can dramatically shift the tone of a relationship.

The burgeoning literature on interpersonal communication celebrates this possibility. As Nichols writes, “. . . when . . . feelings take shape in words that are shared and come back clarified, the result is a reassuring sense of being understood and a grateful feeling of shared humanness with the one who understands.”

The subtext to good empathy is concern and respect, which diffuses hostility, anger and mistrust, especially where these emotions stem from feeling unappreciated or exploited.

Another important benefit of expressing our understanding is that this process may help correct interpersonal misperceptions.

Many scholars have documented the how perception mistakes beset most negotiations; such mistakes are perhaps the foremost contributors to negotiation and relationship breakdown.

Negotiators, for example, often make various attributional errors that is, they attribute to their counterparts incorrect or exaggerated intentions or characteristics based on limited information.

If for example. our counterpart is late to a meeting, we tend to assume that they either intended to make us wait or that they are chronically tardy, even though we may be meeting them for the first time.

In either case, we have formed an attribution or judgment that may prove unnecessarily counterproductive.

By expressing our understanding, we can correct or at least test our attributions about others. By journeying into their shoes, we collect new information and new clues as to their motivation that may help us to revise our earlier assessments.

In a sense, empathy requires us to roll back our judgments into questions or tentatively-held assumptions until we have more complete information.”

***

That’s the extract from the article that I wanted to share.

So, when through perspective taking we are able to demonstrate an understanding of another’s needs, interests and positions we are being empathic. However, it is when we feel understood, as when feelings are reflected back through words that clarify that understanding that we “can dramatically shift the tone of a relationship.”

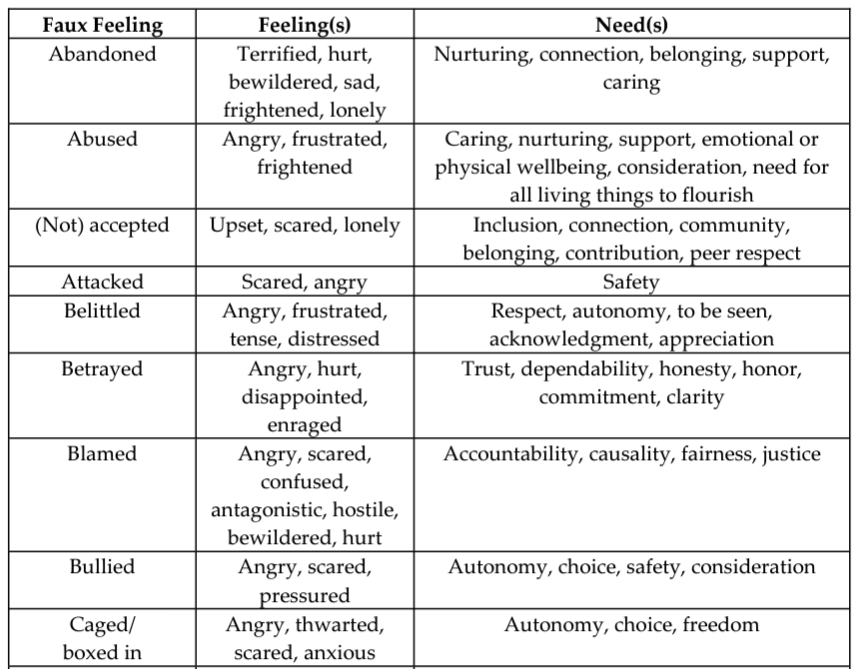

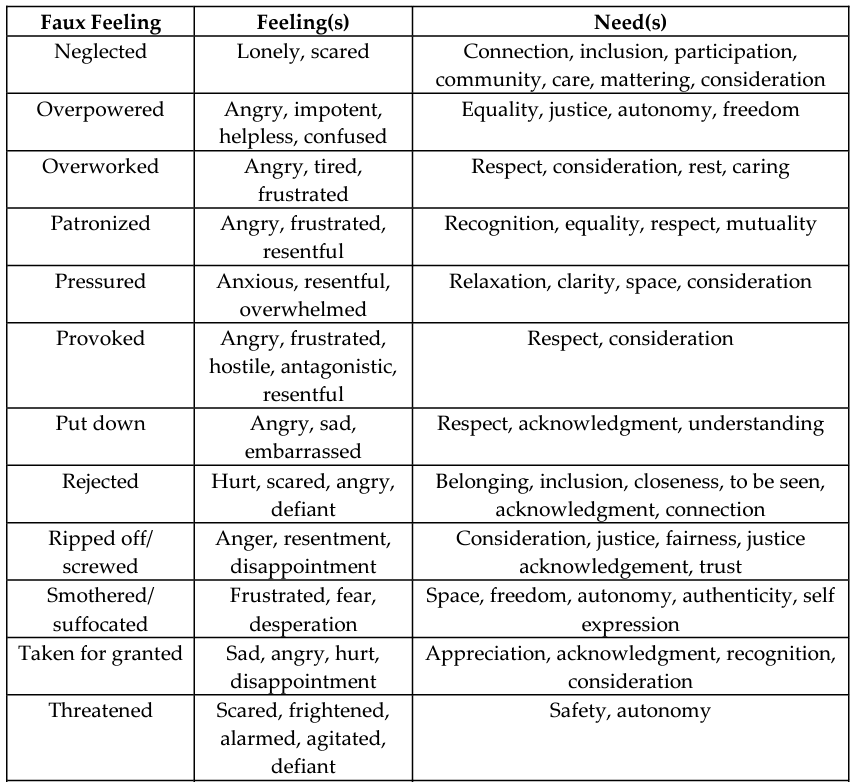

Which is probably why I so appreciate Marshall Rosenberg defining empathy as demonstrating an understanding of another person’s feelings and needs, not just their needs, interests and positions.

Extract from: The Tension Between Empathy and Assertiveness, Robert H. Mnookin, Scott R. Peppet and Andrew S. Tulumello, Negotiation Journal, July 1996.