Avoiding our emotions is not good for our mental health. A psychologist explains how to break the habit and embrace your vulnerability.

BY SABDRA PARKER | MARCH 30, 2023

When was the last time you felt anxious, with your body braced and on edge? It could have been when your partner was late coming home and you couldn’t reach them on their cell, your computer crashed just before a deadline, your child had a full-on tantrum in the grocery store, or you were waiting on medical test results. In that moment, how did you respond?

Maybe you grabbed a bag of cheese puffs, or had a sudden impulse to tidy the kitchen, or found yourself online shopping for that incredibly useful cauliflower corer. Maybe you noticed your racing heart or shallow breathing and started to worry about having an illness. Perhaps you distracted yourself tackling 14 things on your to-do list. Or you had an irresistible urge to check your social media feeds or watch endless TikTok reels of dancing cats. Or maybe you started telling yourself threatening stories (“What if they’ve been in an accident?”; “There’s something wrong with me”; “I can’t cope”; “I shouldn’t be feeling this way”).

In my experience as a psychologist working with clients for 30 years, what is going on in these moments is we are escaping from our inner lives—and this happens when we are confronted with vulnerability. We are triggered by uncomfortable sensations in our bodies heralding emotions stirring beneath, and we do anything rather than face them.

Many kinds of suffering can arise from this. Indeed, research suggests people who avoid emotion tend to have higher pain levels, increased cardiovascular risk, and higher cancer rates, as well as increased depressionn, anxiety, and problems in relationships.

Instead of avoiding what we feel when we are vulnerable, we need to shift our approach. We need to slow down and truly feel our bodies, so we can soothe our nervous systems and access our underlying emotions. When I guide clients to do this, they are able to let go of the urgent need for certainty and control that leads to anxiety problems, release the self-criticism that leads to apathy and depression, and remain present with their vulnerability and benefit from the healthy power of emotion. And this is something you can learn to do, too.

How to recognize unrest

We are always vulnerable, with limited control over the things that matter to us. Maybe you want your brother to quit drinking or your kids to get along or your boss to stop being so critical, or you want to protect those you love from harm or you want an end to world hunger and climate change, or you want this magical moment where everyone is all together at Thanksgiving feeling so close and connected to last forever. Whether we want things we like to always stay the same, or we want things we don’t like to change, it is not entirely in our hands. And just when we are confronted with our vulnerability, a physical feeling disrupts us.

I call this “unrest”: our physical experience of vulnerability, announcing the ideal moment to tune in and spark our growth. And here is the predicament: Unrest causes nervous system activation—a knot in the stomach, braced muscles, shallow breathing, sweaty palms, faster heart rate—and the brain unconsciously interprets this as danger.

This is the moment we usually turn away—toward social media or eating or productivity—but we don’t have to. The first step in embracing our feelings is to differentiate unrest from fear and anxiety. This is not easy to do because unrest, anxiety, and fear activate the same area of the brain and feel identical in the body, despite serving very different functions.

You can recognize anxiety as the avoidant thing you do after unrest stirs you, when you are trying to distract yourself or fix the physical discomfort in your body. Anxiety lets us fantasize that we can control outcomes—the futile “if only” and “what if’s” we often linger upon. Unfortunately, our anxiety lies to us, amplifying (in my experience) our uncomfortable bodily sensations.

Fear, meanwhile, is the core emotion that warns us of immediate threat to life and limb, directing us to fight or flee. Quickened reactions, strengthened muscles, and enhanced lung capacity are lifesaving. In these instances, our physical reactions are not a problem; they are not too much or “stressful.”

If we are afraid of something in the future or the past—anticipating a dangerous possibility or recalling a past danger—we are experiencing anxiety, not fear. This is one of the hardest things for chronically anxious people to accept: that their worry is a story, a prediction, a possibility, but it is not danger.

Four ways we avoid our feelings

Becoming familiar with the ways you typically avoid and escape allows you to tune in even if you missed the initial call of unrest, letting you come home to the body, soothe unrest, and feel. Here is what to look out for.

This essay is adapted from Embracing Unrest: Harness Vulnerability to Tame Anxiety and Spark Growth (October 2022, 274 pages) with permission from Page Two Books.

Minimizing and distracting. We may brush off inner experience as “no big deal.” We might even feel our indifference to discomfort is strength, and there’s no point in feeling, especially when we cannot make outcomes bend to our will. We ignore and neglect our bodies’ signs of stress and may push through our limits until we risk exhaustion, burnout, depression, and physical illness.

For example, my client Aaron didn’t even realize how agitated and tense he was. His habit was to ignore his feelings and just push on at work, blaming himself when things went wrong. His sleep got worse and he became impatient with colleagues. He only started to seek help when his doctor insisted that his gastrointestinal problems were caused by stress.

Control and worry. Sophia came into my office for help with anxiety. “I am too uptight. I haven’t slept properly in years. I wake up at night and just can’t get back to sleep. . . . I get thinking about certain difficulties in my life and I can’t let go; my mind is like a dog with a bone.”

Sophia thought of herself as someone who was tuned in to her body. But the problem wasn’t a lack of attention, it was that she only checked in to “fix” the anxiety, to “make it go away.” Sophia was arguing with reality, feeling she should be a certain way and worrying in an effort to get control and certainty in a world that has neither.

Self-attack. If self-criticism is a deep-seated habit, you may have learned in childhood that your vulnerability leads to abandonment, after being left alone in moments of strong emotions. And so you tell yourself that if you tried harder or were smarter, a better person, more lovable or attractive or stronger or not as gullible or more patient or acted sooner…then things would go better. These lies create a harsh inner environment that can lead to flattened emotional experience, low self-worth, and potentially depression.

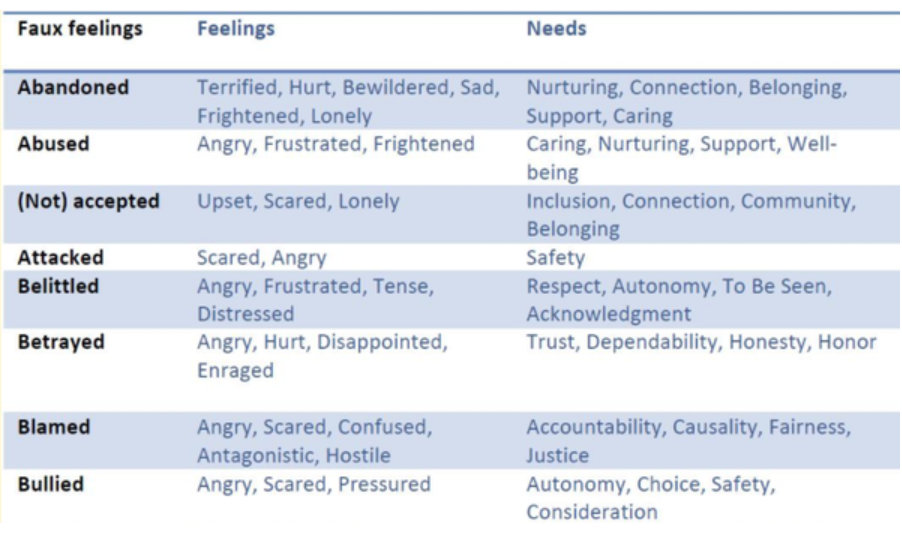

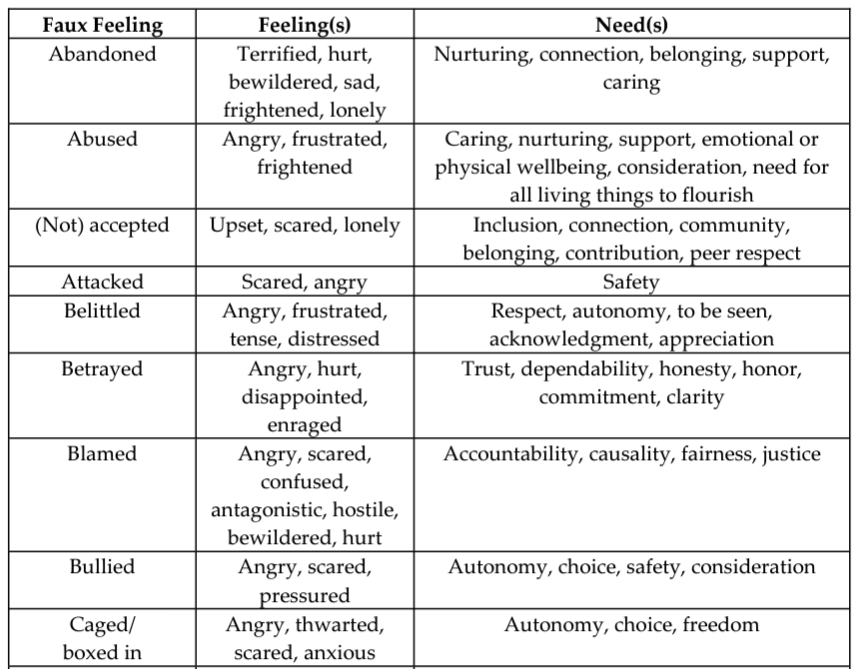

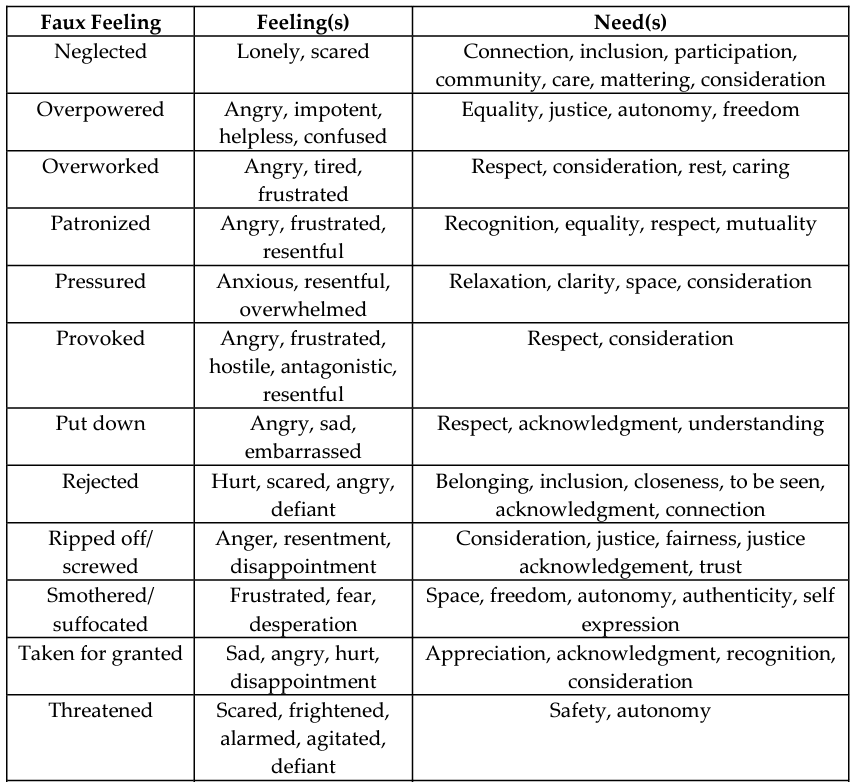

The emotional masquerade. If it looks like sadness and walks like sadness and talks like sadness, is it sadness? Nope. Sometimes other feelings are employed to remove you from pain. If anger was not OK in your childhood environment, you may get weepy and look sad when you get into an argument with your partner. If sadness was regarded as weak, you may appear angry and push people away when you feel sad. You may feel guilty when you feel angry toward someone you care about. These “faux feelings” can keep you stuck if you don’t access the emotions underneath.

How to embrace unrest

Embracing unrest is a journey for life, without a perfect endpoint. It’s about changing your way of being with yourself when you don’t feel good, so when unrest calls, you approach discomfort and access the power of your emotion. Below are two practices to help you rewire your brain to notice and soothe unrest.

1. What’s your ringtone? Like a telephone, unrest has a unique ringtone that lets us know it’s just for us. Our job is to learn our ringtone so we can quickly notice and respond to the call.

In a few sentences, jot down something that is troubling you. Let yourself be aware of the gap between what you want and your ultimate control over the outcome. Pick up your smartphone to video yourself as you describe your vulnerable situation. When you have described it fully, turn off the camera and play the video back.

Observe your body in the video. Be curious, and really “listen” for your ringtone. You have hundreds of muscles, and some will signal more intensely than others—you might notice tapping toes, holding your breath, a furrowed brow, fidgety fingers, or raised shoulders.

Play the video a few times to make sure you have caught all the signals of unrest that you can see. Try to identify your top three sensations of unrest.

2. Say “I DO.” This is a commitment to yourself, like a sacred wedding vow, to tune inward when you notice unrest.

Identify where you feel the sensation; locate it precisely, one place at a time—not just “My muscles are tense,” but which ones and where? Not just arms, but biceps versus triceps; not just tight chest, but where, how large an area?

Describe what you feel using words that capture the quality of your muscle tension and energy, such as:

bracing

constricted

tight

heavy

knotted

clenched

agitated

buzzing

fidgety

jittery

jumpy

fluttery

Observe one specific sensation with the intention of paying slow, deep attention. Ask yourself: “What does that feel like?” over and over.

If your answer is “tense,” then ask, “What does ‘tense’ feel like?”

If your answer is “like a shell,” then ask, “What does that shell feel like?”

Continue this process until you sense a slight release, perhaps a 20% reduction in tension, as your body registers your presence and is soothed. Rest there and feel proud of yourself.

Riding the wave of emotion

Once the body is soothed, we feel safe enough to allow space for the emotions that we have been avoiding. Having guided many clients through this process, I find that it goes something like this: Unrest heralds a moment of vulnerability; something you long for is not entirely in your hands. Your right shoulder grips and instead of ignoring it, you pause, paying careful attention to the tense muscles. After a moment of precise, warm interest, your muscles release and you feel your shoulder drop slightly. Your body registers your awareness and settles.

In that moment, your body understands that, whatever has activated the nervous system, there is no danger—because if there were, you would be focusing outward, not inward. Your body is freed from its prime directive to keep you safe. This safeness opens a channel within you that allows a wave of sadness to come through. This sadness is carrying you to a truth you have been avoiding.

Perhaps you realize you’re working so hard to get everything done but can’t do it alone. Maybe you wish you were more efficient and had more time and energy. But you are indeed only human. The sadness rises and a heavy pressure pulls on your sternum. You breathe into the discomfort as it crests and then ebbs. You find a space inside yourself where you matter. You accept yourself in your limits. You feel less alone, more capable of giving yourself patience and compassion. More able to ask for help.

You might be surprised by the vulnerable truths that emerge when you pay attention to your body:

“I really want this opportunity but can’t guarantee it, and that makes me mad and sad.”

“My body is tight because I’m facing longing and limits in our disagreement.”

“I value our relationship and want to speak my truth, but I can’t guarantee that my protest won’t threaten our bond.”

Getting in touch with your emotions like this can enhance your relationships and have profound mental health benefits. Research indicates that accessing emotion deepens our experience of life’s meaning, buffers stress, aids in decision making, and is a key factor in improved mental health. As well, experiencing emotion is growth-promoting, leading to higher levels of resilience and authenticity.

You are not meant to detach, numb out, avoid, and distract from the pain and beauty of life. You are meant to care deeply without clinging, controlling, or being overwhelmed. Your vulnerability is your strength, and it will grow you. Your emotions are the energy that will transform you and propel you toward your most rich and authentic life.

Sandra Parker, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist and author of Embracing Unrest: Harness Vulnerability to Tame Anxiety and Spark Growth. She earned her doctoral degree at the University of British Columbia, in Vancouver, and is a member of the BC Psychological Association, Canadian Psychological Association, and Canadian Register of Health Service Providers in Psychology.

© 2023 The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley